Textile industry

Stockings for the world market

Information points:

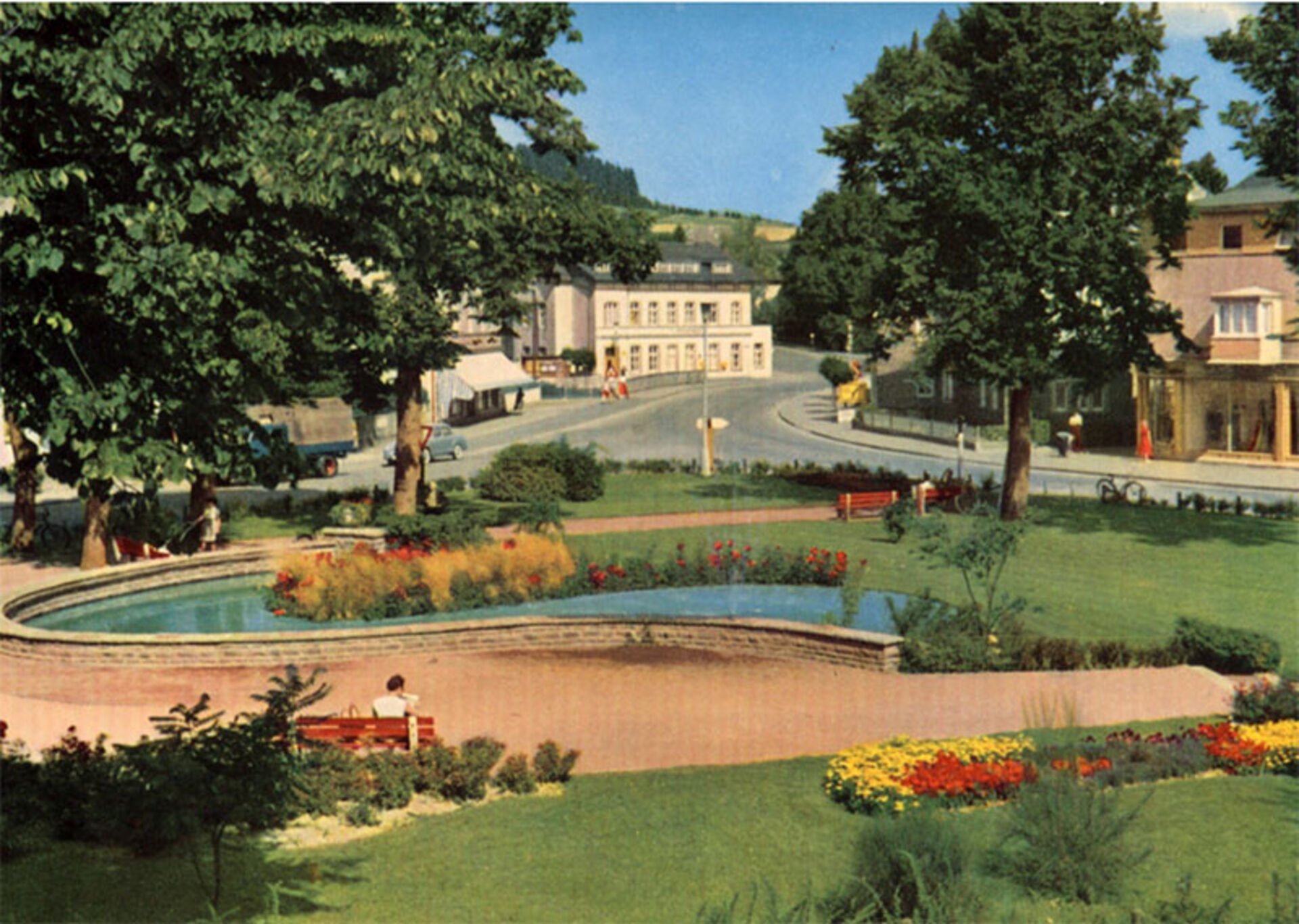

- Bronze memorial plaque Sophie Stecker (house Weststraße 14); on the corner of the street 'Paul-FALKE-Platz'

- Residence Weststraße 12: Entrance to the former Sophie Stecker knitwear factory

Long tradition of wool processing in Schmallenberg

The raw material wool was supplied by local sheep; the yarns were then spun and processed at home. There was a fulling mill for processing woven woolen fabrics as early as 1416 at the Lenne (Auf der Lake), a second fulling mill existed in Grafschaft. Around 1800, the production of woolen stockings in the publishing industry increased. An entrepreneur as a publisher provided the workers with raw materials (wool) and sometimes also working tools (stocking chairs): The work was then done at home. One of the larger entrepreneurs was the town's master rentier Caspar Störmann, who employed home workers on 44 stocking chairs in 1853 (26 of them in his house at Oststrasse 63). He produced so-called "Westphalian jackets" (a whale jacket) as well as butchers' and skippers' jackets, scarves and stockings.

First spinning and knitting mills

From 1850, the Schmallenberg wool industry began to grow. In order to be independent of yarn supplies, Störmann and a partner founded the Störmann & Bitter spinning factory in 1851 in Schmallenberg and produced wool yarn with a selfactor (a spinning machine with a movable carriage that carries the spindles) with 264 spindles and 13 workers. Jacob and Daniel Meisenburg built a second spinning mill on the Lennewiesen in 1865 and in 1867 Michael and his brother Simon Stern founded the third wool yarn spinning mill "Salomon Stern" (named after their father).

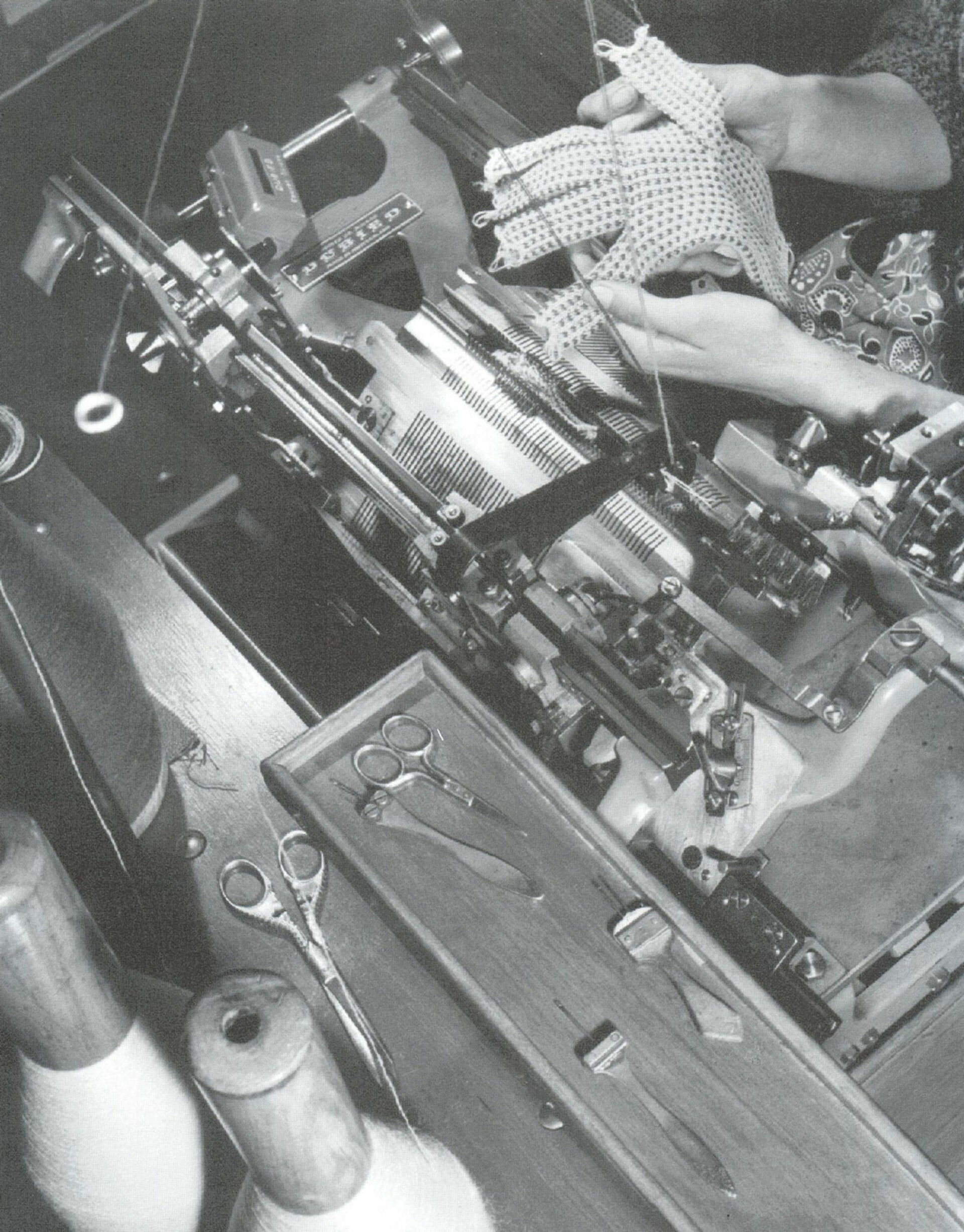

A new phase in textile production began in 1868, when Franz Kayser founded the first knitting factory: the Lamb knitting machine had only been invented in 1863 and the mechanization of knitting had become possible. Most factories (spinning mills, dye works) now also incorporated a knitting mill. The business practices were not always honest: Veltins & Wiethoff (who had taken over Störmann & Bitter as former employees or relatives in 1870) had their workers secretly trained in the use of the machines by one of Kayser's employees. In 1872, they moved the knitting mill into an extension at Weststraße 13. The Stern family also expanded their wool yarn spinning mill into a knitwear factory.

The Stecker company, founded in 1883 by five siblings, focused exclusively on knitting. The siblings worked in shifts and did all the ancillary work themselves. They produced cotton net jackets and woolen stockings. After the death of the eldest sister, Sophie Stecker (1864-1957) managed the company and sales. She presented her products to customers herself at Köln and elsewhere: This was quite unusual for a woman at the time. From 1909, she successfully expanded the product range to include children's clothing.

In 1895, the trained roofer and knitter Franz FALKE set up his own business with ten knitting machines. Just under 10 years later, the Falkes opened their first branch in 1908, and in 1918 they bought the Meisenburg spinning mill. In the 1920s, branches were established in Berlin, Chemnitz, Gelsenkirchen and Bielefeld.

The Sterns founded branches in London (before 1880), Elberfeld (1903) and Balingen/Württemberg (1920). From London, the company achieved global market recognition with branches in Manchester (1908), Glasgow (1908), New York (around 1917) as well as warehouses and sales agencies in Canada, South Africa, New Zealand, Australia and Japan.

Production focus on solid woolen goods

The Sauerländer hosiery industry mainly produced coarse solid woolen goods: jackets and socks. These coarsely knitted standard items set them apart from the fine wool products of their Saxon competitors, met the high demand from the nearby Ruhrgebiet and could draw on a relatively unskilled workforce. This method of production also repeatedly brought in military orders: During the Franco-Prussian War of 1870/71, German soldiers wore Störmann jackets and Kayser socks; Stecker produced underjackets, head and ear muffs during the First World War; during the Second World War, production was considered vital to the war effort, which also resulted in the use of forced laborers.

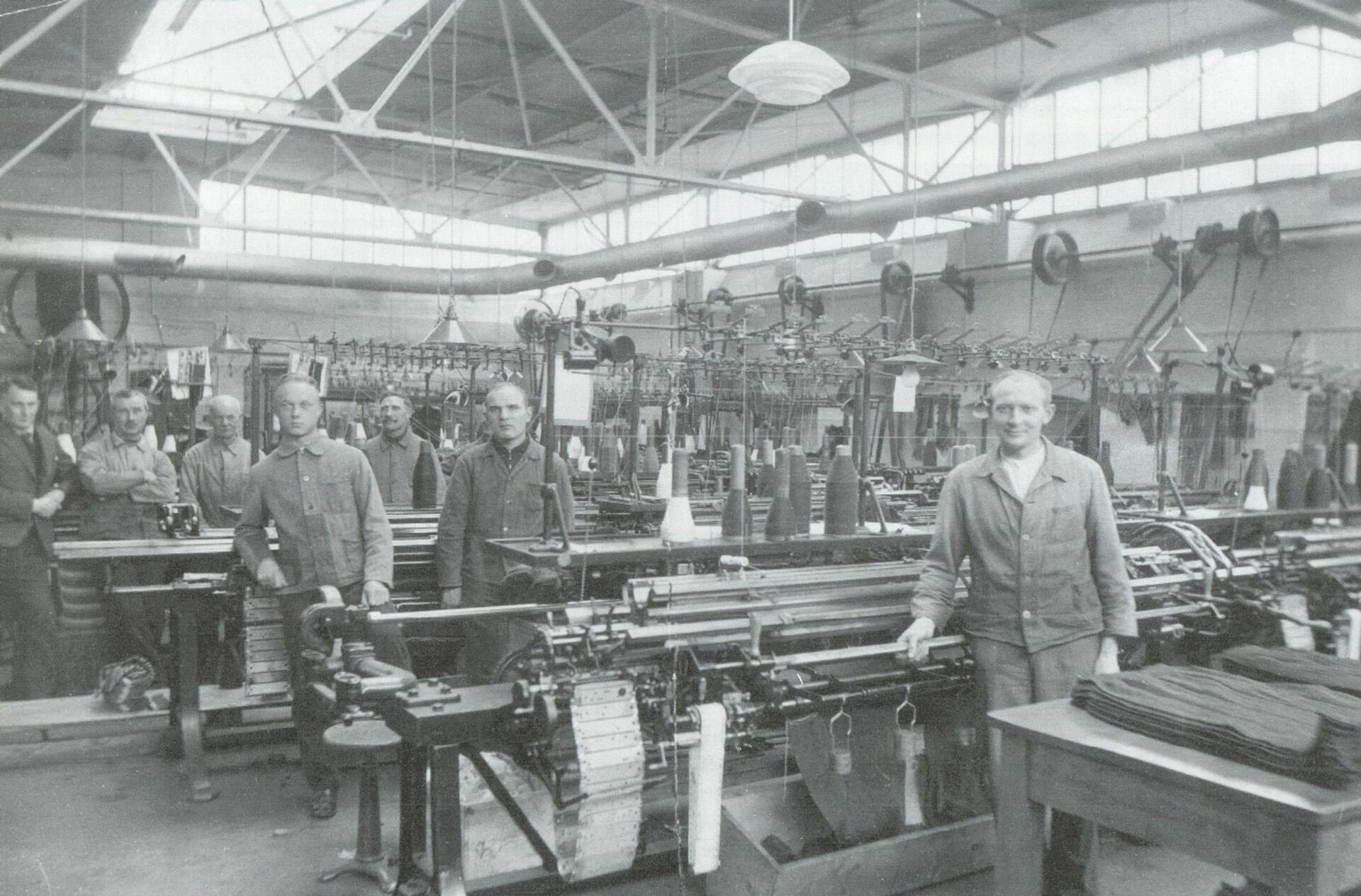

Homeworking and publishing continued well into the 20th century. By 1960, however, most companies had centralized branch factories where 15 to 120 workers - all women - carried out simple tasks on machines: they fitted the lengths, closed the toes of stockings on warping machines or sewed hoses together. Working hours changed enormously: in 1900, they worked 58 hours a week; in 1918, the working week was reduced to six days and 48 hours. The 40-hour week dates back to the 1960s. During the First World War, the age limit for working people was lowered from 70 to 65. Patriarchal conditions prevailed: Obedience was a matter of course. However, the boss also looked after the workers and was always present. Veltins & Wiethoff was the largest company in Schmallenberg before 1914 with 100 employees; FALKE expanded rapidly after the First World War and had several hundred employees in the 1920s. Stecker employed 200 workers until 1945, the Sterns 120 until 1938. Numerous smaller companies were also active.

During the National Socialist era, the company continued to manufacture stockings, workwear and unistrick outerwear (Stern) and baby underwear (Stecker). FALKE bought the Stern company in 1938 as part of the "Aryanization" process. During the war, forced laborers and Eastern workers were often used. Towards the end of the war, production came to a standstill in most companies. During the conquest of Schmallenberg on April 7, 1945, the Stecker factory was destroyed; the Veltins & Wiethoff factory was closed by the Americans.

Structural change after 1960

Production slowly started up again. Undaunted, Sophie Stecker and her nephew set about rebuilding their company. Numerous expellees from the East found work in the textile factories. By 1950, 1,800 people (two thirds of whom were women) were once again working in the town's textile factories. In the 1960s, production was running at full speed: guest workers were hired. 90% of Schmallenberg's jobs were directly or indirectly dependent on the textile industry. FALKE became the largest employer.

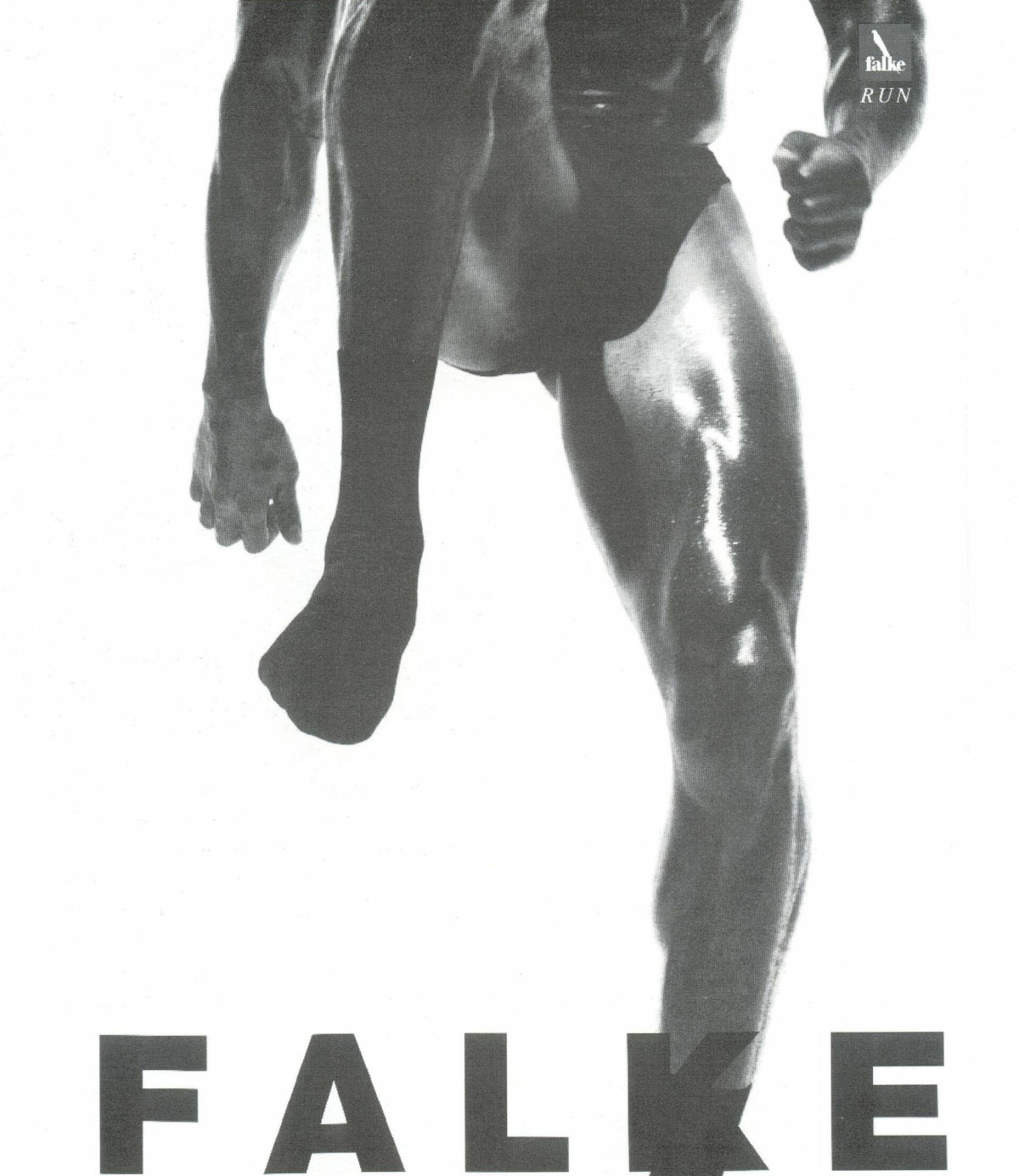

At the end of the 1960s, expansion came to a halt due to increased competition (cheap imports from the Far East), the effects of the structural crisis in the Ruhr region and changing consumer habits. By 1980, only around 30% of jobs in Schmallenberg were still in the textile industry. Some of the traditional companies, including Veltins & Wiethoff in 1974, had to close, while others relocated production to low-wage countries, closed branches or expanded their collections. FALKE was able to successfully maintain its position on the market by changing and relocating production. The company had been producing nylon hosiery since 1958, entered the production of sporting goods in 1970 and created production niches and unique selling points with designer fashion.

Sophie Stecker was the youngest of six children in a long-established Schmallenberg family. Her older sister Therese Stecker trained as a knitter in 1870/71 in Köln and then trained workers herself in Biedenkopf. From 1883, the Stecker family produced cotton net jackets and woollen stockings in shifts in their parents' house at Weststraße 14, which were sold in the Rhineland and in Westfalen. Despite all their hard work, money was scarce, so they worked on salary until the first machine of their own was saved up and a wholesaler was found for the stockings. Sophie herself worked as a foreman in external knitting mills and saved up money to buy two second-hand knitting machines, which she contributed to the family business.

In the 1890s Sophie Stecker moved to Köln and sold her knitwear herself, which was very unusual for a woman at the time. In 1903, the Stecker company set up its own production building at Weststraße 12. On May 12, 1906, the company was registered in the name of Sophie Stecker by the commercial court - after the death of her sister Therese, Sophie ran the company.

In 1909, she installed motorized knitting machines and by 1913, all hand knitting machines had been replaced by motorized machines. From 1927, she created a promising sector by switching to baby clothes and infant clothing. Young women preferred to go to work at Sophie Stecker's: there was a pleasant atmosphere and baby clothes were produced.

The factory was destroyed in the last days of the war in 1945; undaunted, Sophie Stecker had the factory rebuilt in a modern style by 1953. On her 90th birthday in 1954, Sophie Stecker was made an honorary citizen of her hometown: she made a significant contribution to the city's development, Schmallenberg to making the city a textile-industrial city.